“Missandei Deserves Better:” Loving Blackness through Critical (Anti)Fan Uptakes and Disruptakes

To face these wounds, to heal them, progressive black people and our allies in struggle must be willing to grant the effort to critically intervene and transform the world of image making authority of place in our political movements of liberation and self-determination."

- bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation

Table of Contents

- Tracing White Supremacy in canon compliant Uptake,

- Resisting White Supremacy through Critical (disr)uptakes: On Loving and Caring For Missandei

- Conclusion: Why Missandei Deserves Better.

Content warning: White supremacy, descriptions of death.

In the final season of Game of Thrones (GOT), Missandei is brutally executed in front of her loved ones. Queen Cersei, the main antagonist of the show, captures Missandei to demonstrate her power to Daenerys, Missandei’s close friend, as they fight over the throne. Missandei is forced to stand on the wall surrounding Kings Landing — a stage for her death — with her hands bound in chains (Figure 1). Her loved ones, including her romantic partner Grey Worm, watch as Cersei gives the signal that prompts Missandei’s death.

GOT’s writers are known for their brazen choices in killing characters, beloved or hated. Missandei’s death is just one of many that the audience witnesses. Throughout most of the show, every characters’ demise affirms there are happy endings in the GOT universe. Yet, in the final season, the writers offer happy — or as happy as can be — endings for several characters, including Arya, Sansa, and Jon. Sure, they survive extreme violence and live with trauma, but they each get what they want. Missandei’s death, in this context, hurts. She did not get her happy ending with Grey Worm. They could have sailed to Naath, her homeland together. Her death, then, resonates differently than most other characters, a type of violence that feels all too real in the face of colonialism and white supremacist systems of power. Missandei, portrayed by Nathalie Emmanuel, is one of the only Black women in the show. She survives slavery and dedicates her life to liberating others alongside Dany and Grey Worm. She breaks her metaphorical — and literal — chains. Yet, as WriteGirl points out, “she dies in chains, basically in a pissing contest between two White women.” Her liberation arc, her happy ending, is stifled the moment chains are placed back on her wrist.

Even before her death, Missandei often lingers in the background with barely any time spent towards developing her character. As Ebony Elizabeth Thomas (2019) argues: “Although Missandei is free, her story remains tied to Daenerys.” Thomas’ argument resonates with Writegirl’s observations on how the fandom represents Missandei. Writegirl expands upon Thomas’ argument, claiming that when Missandei is included in fics, she is often there to just affirm Dany; Missandi is “window dressing. She's there, she doesn't speak, or she speaks, it's one or two sentences in the entire fic.” While the trends from both the show and the fandom overlook Missandei, the glimpses of Missandei’s story apart from Dany are some of the most beautiful moments on the show. For example, in season 5, Missandei tends to Grey Worm’s wounds after a battle and they share their first kiss (Figure 2). He confesses he loves her, even after he survived years of torture conditioning him and other Unsullied that he could never love anyone. “I am ashamed because...I am afraid...I fear I never again see Missandei from the Island of Naath.”

In order to trace fans’ critical uptakes and critical disruptakes, I build upon Thomas’ blog post to examine how fans critique Missandei’s death and the erasure of Black women in the show and fandom. Specifically, I use approximately 29,000 GOT fanfictions published on Archive of Our Own (AO3), a popular fanfiction publishing website. Fans flock to AO3 to compose, read, and engage with fanfictions of their favorite movies, television shows, books, and characters. Every work published on AO3 can incorporate metadata for discoverability purposes, such as using the Additional Tag “Missandei deserves better”. I examine how fans critically uptake Missandei’s death, especially in the context of a fandom and show dominated by whiteness, such as through the use of Additional Tags like “Missandei deserves better” and how fans reimagine justice for Missandei. Rebecca Wanzo (2015) argues, “Black fandom can thus be both counter to white hegemony and normative in its adherence to ideological projects that treat black people as representative of US culture instead of outliers.” For Wanzo and other scholars studying anti-racism and Black cultures, the work of Black fans and allies is not just to combat white supremacy, but to make explicit the interchangeability of blackness; popular culture; and dominant ideologies, politics, and histories.

I begin this piece by demonstrating the white supremacist ideologies embedded in GOT, and in the next section examine how the GOT fandom on AO3 reinscribes them. The crux of this piece shows how several fans challenge this white supremacy through their composing practices, critical uptakes, and critical disruptakes. Critical fans and critical uptakes are necessary to intervene when fandoms and popular culture texts uphold white supremacy in order to celebrate “loving blackness” (hooks, 1992) as an act of resistance, survival, and resilience. I also examine antifandoms, or fan communities that revolve around critiquing or disliking a media text; often antifandoms are simultaneously critiquing a show’s reification of white supremacy or other harmful ideologies, while also enjoying other aspects of the show. I look at one instance of a critical disruptake as an antifandom practices, in which a Black fan author disrupts the seemingly normal fanfiction genre approach in order to critique both GOT and the fandom.

Tracing White Supremacy in canon compliant Uptake

GOT valorizes whiteness, both overtly and insidiously. As Sarah Florini (2019) points out, GOT is a “show coded as white, featuring all white leads.” The only few characters of color, like Missandei, meet violent ends and/or are portrayed as savages. The Dothraki, a nomadic tribe east of Westeros, are feared across the continents, and their culture revolves around violence and bloodshed. Grey Worm is part of the Unsullied, an army of child soldiers who are conditioned to feel no compassion or love so they are more effective in battle. The writing in the show wrestles with the idea of Westeros’ racist assumptions towards the people of Essos, the land across the sea. For example, when Grey Worm and Missandei are in Winterfell, people stare at them unprompted because of their appearance, marking their difference. Yet, even when the show attempts to critique this racism, it reinscribes this racism by affirming the people of Westeros’ fears. Dany and her army of the Unsullied and Dothraki destroy King’s Landing, substantiating the racist fears woven across Westeros. And Missandei’s murder for a White woman’s political gain, the lack of writer’s attention to her character, and the disruption of Missandei and Grey Worm’s happy ending reifies this white supremacy.

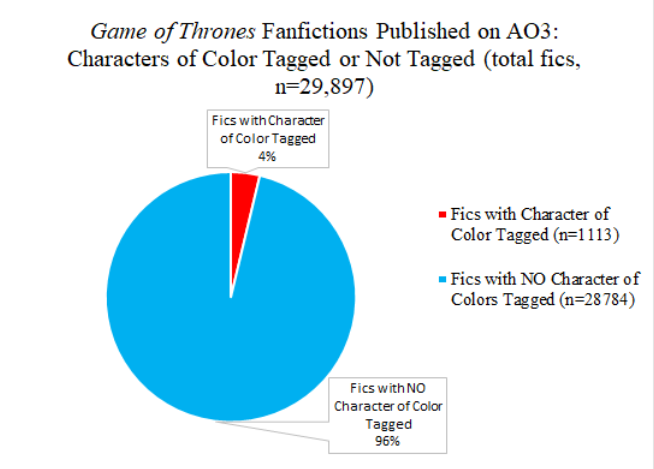

White supremacist ideologies are replicated in the majority of the GOT fandom, especially on AO3. Fandoms are entangled in the same systems of power as popular culture; cultural hegemony permeates across media, from mainstream to fan-made media. Only four percent of the 29,897 GOT fanfics published on AO3 incorporate characters of color. This data is based on the GOT AO3 data collected for this dissertation from the first GOT fanfic published up until October 2019. Figure 3 shows a pie chart of all the fanfics with character tags, as not every fanfic author uses character tags. I separated the fanfics with character tags by whether a character of color was incorporated or not. To do this, I created a list of all the characters in GOT played by actors of color who are not fantastical creatures. If a fanfic character tag incorporated one of these characters, it was labeled as “Fics with Character of Color Tagged.” This low percentage demonstrates how fans commit to main, well-developed characters, which the GOT writers never granted Misasndei. GOT writers fail to provide characters of color the same spotlight and invest space to their development. The lack of development and screentime may contribute to lesser fan investment.

The erasure of characters of color in the GOT fandom reinscribes white supremacist systems, whether they intend to or not. This erasure is also a form of canon compliant uptakes in which fans take up canonical details and ideologies from the show as they write their fanfiction (Messina, 2019). Canon complaint uptakes, based on the AO3 additional tag “canon compliant” are when fans follow what is canon in their transformative fanwork. In this way, canon compliant uptakes mirror canonical events and generic conventions from the original texts they love. The term “canon compliant” is a well-used Additional Tag on AO3 that fan authors use to signal to their audience that they are following the canon and thus appreciate the canon. canon compliant uptakes do not inherently have particular ideologies, such as white supremacy, embedded within them.

I first want to briefly define uptakes and why uptake is an important framework. Uptakes as defined in rhetorical genre studies are the anticipated generic responses to specific genres; these uptakes are deemed appropriate responses in particular contexts that have been deemed appropriate based on place, time, frame, and function. There are often particular anticipated conventions within these responses, conventions determined by context, community, and ideologies (Freadman, 1994 & 2002). Writing fanfiction is a form of uptake enactment, or the action of taking up and responding to one genre with another (Dryer, 2016). Uptake can also demonstrate the roles of power, privilege, and ideology within generic boundaries and conventions (Bawarshi, 2000 & 2016) — why are particular uptakes anticipated in particular contexts? How do these uptakes resist or replicate particular ideologies?

Canon compliant uptakes, then, typically mirror the ideologies embedded in the original text because they follow the canon. So, GOT canon compliant uptake artifacts — such as the AO3 fanfics published — are bound in the same systems of white supremacy as the show. What makes examining uptake so important is it emphasizes the agency of the person doing the uptake — in this case, the fan author. Fan authors have the abilities to resist and speak back to harmful ideologies. And they also have the ability to replicate those ideologies.

To point back to Thomas’ argument about Black characters’ stories being tied to White characters, how do fans uptake this relationship? To again quote Writegirl, GOT fanfictions often depict Missandei as “window dressing.” This, of course, is Writegirl’s observation, although the small percentage of GOT fanfics that include characters of color affirms her point. However, when Missandei’s character tag is used, how integral is she to the fanfic? First, out of the 29,897 fanfics, only 1,108 (3.4%) use Missandei as a character tag, as opposed to other White GOT side characters who appear more frequently across the fanfics: Gendry at 12.2%, Lyanna Mormon at 5.3%, Tormund at 5%, and Podrick at 5.6%.

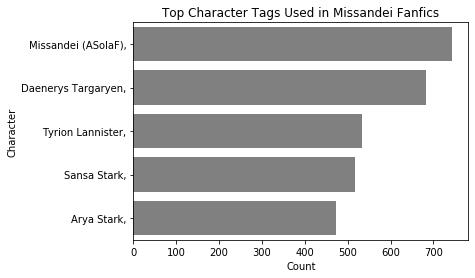

Merely pointing out how often Missandei’s character tag is used across the entire GOT corpus does not emphasize just how much Missandei is erased from fanfics. I created a small corpus of these 1,108 fanfics that use Missandei in the character tags to get a better sense of how she may appear in these fanfics. I used the Python function “string contains” which pulls any fanfics that use the word “Missandei” in the character tags, which includes different uses of Missandi from “Missandei (ASoIaF)” and “Missandei.” To learn more about the computational process, read the “Missandei Deserved Better” Computational Essay. Figure 4 shows the results of the most popular characters and relationship tags in the Missandei corpus. Because the character tags are not all normalized, “Missandei (ASoIaF)” is used 744 times while “Missandei” is used 68 times. Daenerys’ character tag is used 682, followed closely by Tyrion, Sansa, then Arya. Grey Worm, Missandei’s partner, does not even make the top five, suggesting that their relationship may not be a focus even in the Missandei corpus; Grey Worm appears 396 times, or in only 35.7% of the fanfics published in the Missandei corpus. This suggests that there may be less of a focus on Missandei and Grey Worm’s relationship in these fanfics, as the most used tags are Dany and Tyrion. Again, Writegirl’s theory of Missandei being “Window dressing” comes to mind.

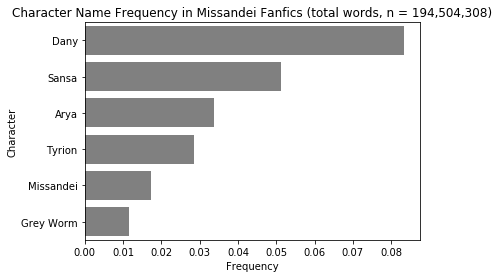

Beyond metadata, then, is how often her name actually appears in the fanfics and compared to other popular characters who are tagged in this corpus. The use of names may be misleading, as some authors may write in first person or use alternate ways of pointing to a character. Still, as the results show, Missandei’s name appears far less frequently than many of the White characters mentioned, suggesting she is not nearly as central to the fanfic as these other characters. Figure 5.5 shows the word count of how often the names “Missandei” and other characters appear in the Missandei corpus. Even in her own corpus, Missandei’s name (or Missy) is used less frequently than Daenerys (or Dany), Sansa, and Arya, who are all popular White characters. Fanfic authors who incorporate Missandei mirror how GOT writers incorporate her — she is, as Writegirl argues, “window dressing” who rarely gets her own story. I even searched how frequently “Naath,” Missandei’s homeland, is used (the answer is 0.0005%) versus Westeros (0.005%), suggesting again that her background is not a key component of these stories.

Fans’ cannon complicit uptakes of the GOT show and A Song of Ice and Fire demonstrate how representations of systems of power, like white supremacy, are replicated in fan genres. Fans’ choices about which characters they value, which characters they ship, and how they reimagine particular characters reveal their values about whose stories they believe deserve to be centered. Unfortunately, these values often overlook characters of color, particularly Black characters like Missandei. The violence enacted upon her in GOT’s final season is reinscribed as she is forgotten or paraded as “window dressing.” White supremacy is simultaneously insidious and overt, and often difficult to untangle. Yet, there are fans whose uptakes challenge white supremacy, and there will always be fans who resist harmful ideologies in their uptakes.

Resisting White Supremacy through Critical (disr)uptakes: On Loving and Caring For Missandei

Fandoms are not homogenous, and there are individual fans and communities of fans who challenge white supremacy. Not only through the explicit critiques of white supremacy, but also through, as bell hooks (1992) argues, “loving blackness.” hooks argues “In white supremacist context, ‘loving blackness’ is rarely a political stance that is reflected in everyday life” (p. 10). To love blackness is to value Black joy, romance, diasporic cultures, and people. The way Missandei is taken up in the GOT fandom reflects the infrequency of loving blackness. But there are fans who love Missandei, who cherish her relationship with Grey Worm, and who, through their uptakes, represent what loving and protecting Black women can look like in a culture of white supremacy. This section examines these fans’ — and antifans’ — critical uptakes and critical disruptakes of Missandei’s death.

In The Dark Fantastic (2019), Ebony Elizabeth Thomas argues that the way Black women characters are written in popular culture follow the narrative arc of the Dark Other, or a cycle of generic conventions. Thomas demonstrates how these conventions are embedded in so much pop culture media and are due to an “imagination gap” in pop culture and literary representation. One step in this narrative cycle is “haunting,” which occurs after the “violence” cycle — the haunting is how the violence Black women characters survive or die from resonates throughout the texts. She looks, for example, at Rue from The Hunger Games, a young Black girl who dies in the main characters’ arms; her death and the main character’s compassion spark a revolution. Missandei’s death also leads to Dany making a choice — committing genocide against the entire King’s Landing people. Her final words — “Dracarys”, or Dragonfire in Valyrian — haunt the last few episodes of GOT as Dany, Grey Worm, and their armies destroy King’s Landing, murder its people, and suffer the consequences.

Critical uptakes of Missandei’s character and execution, though, align with Thomas’ call for “critical counterstorytelling for a digital age” (p. 10), in which emancipation is the final step in this Dark Other narrative arc. The Black characters Thomas centers her book around such as Rue from The Hunger Games and Gwen from Merlin, are rarely offered this emancipation. It is up to fans and critical counterstorytellers to reimagine their emancipation through the use of critical uptakes. How, then, are critical fans already imagining and taking up Missandei’s emancipation?

One digital space to examine “loving blackness” is the #DemThrones hashtag is used across Twitter, Instagram, and other platforms. Black fans and fans who are allies/accomplices used #DemThrones while the show was airing in order to live Tweet their reactions to their show as well as find like-minded fans. Florini (2019) describes #DemThrones fans as “able to shift their contributions to a parallel timeline, separating themselves from the fans using the official hashtags while still allowing them to utilize Twitter for synchronous coviewing.” Black fans often carve out spaces separate from fandoms that are either predominantly White or replicate white supremacy, whether through the implementation of hashtags or creation of other media, like podcasting. AO3 does not always offer the same counterspace that other digital platforms offer, as the data demonstrates how fans may uphold — even accidentally — white supremacy. However, there are fan authors who perform critical upakes on AO3, challenging the white supremacy laced in both GOT and the GOT AO3 fandom.

Critical uptakes are when writers “resist harmful and exclusive cultural ideologies in their uptake” (Messina, 2019)In this instance, critical fans are those who enact critical uptakes, analyzing how the generic conventions from the original show or fanfictions valorize particular, exclusionary ideologies. Through this analysis, fans recognize the systems of power at work in these generic conventions and challenge them in their own fanfiction. Specifically, fans’ critical uptakes of Missandei demonstrate not only their care and love for her, but the recognition that she “deserves better.” On AO3, only a few fanfictions use the additional tag “Missandei Deserves Better (ASoIaF)” or a similar tag, signaling fans’ mourning of Missandei as well as the recognition that she was subjected, like many Black characters are, to an unjust violence and death.

“The Liberated Voice”: Cases of fans’ critical uptakes

WriteGirl, whose full interview can be found in “Interviews”, provides one version of Missandei’s arc. Her fanfiction, “OtherWhen: Game of Thrones” is a collection of short vignettes reimagining particular moments in the show. Chapter 10, titled “In Which Missandei Takes Control of Her Fate,” reimagines Missanndei’s death, where she refuses to be used as a political pawn. Writegirl cites her motivation for critically taking up Missandei’s death as frustration towards the writers — not only that she believes Missandei’s final words were out of character, but that the writers undermine Missandei’s liberation arc by choosing to have her “die in chains.” While the frustration Writegirl felt was the exigence of her piece, she also argues that not enough fanfics focus on Missandei, and she wanted to provide space for that. She says, “Kind of like, who is Missandei? If you take away slavery, and her being Daenerys' friend, who is this person? What is the one thing that would be important to her?” Writegirl’s point that Missandei is often written alongside Dany mirrors’ Thomas’ analysis of the show in that Missandei’s story is “always tied to Dany’s.” In Writegirl’s fanfic, Missandei does reflect on her relationship with Dany, but also about her liberation and desire to see others liberated. She also tries to remember her home before she was enslaved, always tying her story back to the sands of Naath, her birthplace.

In Writegirl’s piece, Missandei’s arc still concludes with her death, although Misandei chooses how she dies and takes Cersei with her. It is not Missandei’s death, though, that demonstrates Writegirl’s critical uptake, but the moment before — Missandei’s choice to speak back to Cersei. They are not words to Dany, Grey Worm, or the army standing before the wall — Missandei speaks directly to Queen Cersei, who has imprisoned her. She says, “You would have fit in well with the masters in Astapor.” The “masters” here refer to the people who enslaved Missandei and others. When I asked Writegirl about this moment and why she chose to have Missandei speak to Cersei, Writegirl explains, “She's really seeing Cersei for the creature Cersei is, beyond just being kind of a high-born woman in Westeros. She's seeing the monster that's inside Cersei.” While Cersei is well-known in the fandom to be evil, her status as Queen demonstrates how she is able to manipulate those around her to gain her position of ultimate power. She may not be a beloved Queen, but she is the Queen nonetheless. Missandei, however, refuses to acknowledge Cersei’s power and chooses to talk back.

This moment resonates with bell hooks’ theorizing in Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black on the oppressed using speech to combat their oppression:

"Moving from silence into speech is for the oppressed, the colonized, the exploited, and those who stand and struggle side by side a gesture of defiance that heals, that makes new life and new growth possible. It is that act of speech, of “talking back,” that is no mere gesture of empty words, that is the expression of our movement from object to subject—the liberated voice." (p. 9)

The choice to have Missandei “talk back” to Cersei here — to carve out her own space and speak truth to power — demonstrates how Writegirl is thinking through both characters’ positionalities and another form of liberation. One of the goals for Missandei, Writegirl argues, is to help liberate all those who are enslaved. By choosing to speak back to Cersei, comparing her to a “master,” Missandei recognizes a different form of oppression, not as overt as slavery, but still oppressive nonetheless. Cersei will do anything to maintain power, and in this drive, enact violence upon those around her and the people she is ruling. She, as those in positions of great power often do, forces armies to go into battle to protect her crown and her position. She reigns as a totalitarian dictator, determining who is allowed to live and die. Missandei sees this and speaks up in a “gesture of defiance” (hooks, p. 9). While Missandei still dies, she uses her “liberated voice” to stop Cersei from continuing to enact systemic violence upon others. She also does not call for Dragonfire, so her final words do not haunt King’s Landing, then, leading to the destruction of an entire city.

While Writegirl is the only fan author who was interviewed for this dissertation, there are other fan authors who have critically taken up Missandei’s story and narratives about race, liberation, and Black love. I pulled three fanfics — two published in the corpus I collected and one published more recently (October 2020) — that demonstrate Thomas’ critical counterstorytelling by reimagining Missandei and Grey Worm’s fates. These fanfic authors center Missandei’s well-being as well as her and Grey Worm’s love for each other.

In Lady_R’s “The Girl Who Got Away”, Lady_R still incorporates the moment Missandei stands on the wall before her loved ones, but reimagines only her ear being cut off in order to still have a catalyst for the burning of King’s Landing. Missandei survives and escapes, watching the destruction Dany brings upon the city and losing faith in her once friend. She finds Grey Worm and tends to him as they exchange promises of love. The story progresses by focusing on exchanges — their choices, their actions, and their emotions — between Missandei, Grey Worm, and Marselen, Missandei’s brother. There is a conflict between Grey Worm and Marselen early in the piece, as Grey Worm continues to slaughter soldiers after they surrender. Grey Worm’s choice to continue this slaughter is partially due to his conditioning to follow commands — commands specifically coming from Dany — as well as his anger that Missandei is missing. Before he is reunited with Missandei, though, Marselen convinces Grey Worm to help survivors instead of slaughtering, thus defying Dany and resisting his own conditioning. He chooses then to help keep everyone safe by calling his soldiers to:

“-Find the survivors!-. Grey Worm’s throat itches as he screams the new command, but he repeats it once more, and twice again in the Valyrian tongue. -Find them. Keep them safe! This is not who we are! This won't be who we are!-.”

His refusal to continue slaughtering, following Dany’s lead, demonstrates the strength of his identity separated from Dany, especially when he says, “This is not who we are! This won’t be who we are!”

Just as Grey Worm defies Dany, so does Missandei. Lady_R actively critiques the “window dressing” convention in fanfics that Writegirl points out, in which Missandei appears in fanfics merely to affirm Dany. In Lady_R’s piece, though, Missandei, upon seeing the destruction Dany reigns upon King’s Landing, realizes Dany is not the person she thought. Missandei defies Dany, both in thought and action. Missandei helps survivors find shelter away from Dany and her dragon, commands the Dothraki from Dany’s army to do the same, and realizes that Dany has never cared about liberating others when Missandei thinks, “So much for the Breaker of Chains.” Lady_R highlights Missandei’s agency, separate from Dany, even emphasizing the philosophies which Missandei lives by: “But the way of the Naathi is to grow what we can from burned terrain.” Missandei is a survivor; she survived being enslaved, she survived Queen Cersei and Dany’s dragon, and she will continue to endure, as generations of her ancestors taught her on Naath.

Finally, Missandei and Grey Worm reunite, demonstrating Lady_R’s commitment to representing Missandei’s joy and emancipation, as Thomas calls for. In the last scene of the fanfic, Missandei asks Grey Worm if he is afraid of Dany, and he says, “I had one fear, remember that. A fear that I left behind.” This quote calls back to the scene from Season 5 of GOT s when Missandei and Grey Worm first kiss. Lady_R’s call back demonstrates the importance of representing romance and joy for Black characters in popular culture texts. Lady_R’s focus on Missandei and Grey Worm’s arcs, their choices to defy Dany, and their final reunion signifies how fanfic authors can challenge white supremacy and other systems of power in their uptakes.

While I focused on Lady_R’s actual fanfiction text, I also want to bring to attention the ways fan authors use Author’s Notes, or the brief author’s explanations at the beginning and end of fanfic chapters. In her piece, “The Fire It Ignites,” supergirrl chooses for Dany to die rather than Missandei, imagining how Missandei may navigate her new leadership role. The piece centers Missandei’s interactions with other characters and the different cultures from Meereen, the land to the East of Westeros. In supergirrl’s first Author’s Note in chapter one, she critically takes up the show and uses the Author’s Note as a place to directly address what she perceives as problematics in the show; she simultaneously critiques the show’s ideologies while also affirming that these issues motivated her to write. For example, she points out that the Dothraki culture is all but erased in later seasons of the show. She writes, “My love for [Missandei] and Daenerys, as well as my interest in other things that the show bungled/left out (Dothraki culture, the existence of Dothraki women, women having relationships with each other not based on spite and possessing complex internal lives, etc) inspired me to write this fic.” The Dothraki in GOT are a nomadic culture that Dany leads; in the show, their cultural practices are often portrayed as barbaric and violent, and the people of Westeros are afraid of the Dothraki. The show plays into the notion of nomadic tribes, particularly non- White nomadic tribes, as being savage, continuing to reinforce a white supremacist ideology that both led to and stems from colonialism. While the show at first provided more sympathy and time dedicated towards the Dothraki, the final few seasons only showed them during battles when they were either being slaughtered or doing the slaughtering. supergirrl emphasizes this in her Author’s Note and proceeds in the actual fanfiction text to better explore the Dothraki people, especially Dothraki women. Her Author’s Note here acts as a bridge between her criticism of and her reimagintion of the show.

For supergirrl, as a critical fan, she is invested in centering the cultures and characters that the show overlooks, especially those that are coded as non- White. Her Author’s Note also demonstrates how she is writing within a particular political discourse specifically found in scholarship on slavery. She writes, “I have also chosen to use the word 'slave' in dialogue, as that what is used in canon, but in Missandei's thoughts she uses the more appropriate 'enslaved person/people.'” supergirrl points to the difference in using the adjective “enslaved” to describe a person versus the noun “slave.” This acknowledgement of adopting careful language to talk about slavery points to the suggestions and arguments made by P. Gabrielle Foreman and collaborators in “Writing about Slavery/Teaching About Slavery: This Might Help.” Foreman writes that using the adjective “disaggregates the condition of being enslaved with the status of ‘being’ a slave. People weren’t slaves; they were enslaved.” Whether or not supergirrl is aware specifically of Foreman’s work, she is aware of the discourse around slavery, specifically the discourse that challenges “ assumptions embedded in language that have been passed down and normalized” (Foreman). supergirrl’s acknowledgement demonstrates her own critical awareness of the power language wields, especially when storytelling and counterstorytelling. Her Author’s Note demonstrates how fans may critically uptake the shows and popular culture materials they love. Critical uptakes can be performed in both meta genres, such as the Author’s Note, as well as in the actual fanfictions themselves. supergirrl subverts the show’s and the fandom’s white supremacy by reimagining Missandei’s story and importance, the representation of the Dothraki people and culture, and the use of language in reinscribing or challenging systems of power and oppression.

Critical Disruptakes in Antifandoms

Black fans, fans of color, and allies often need to carve out their own spaces apart from mainstream fandom spaces, like AO3, or reimagine how discourse and connection operate within these platforms to create community. Using platforms’ different affordances for community-formation, such as Additional Tags on AO3 or hashtags like #DemThrones on Twitter, is one method in carving out these spaces. The community-making mechanism of carving out space and resisting white-dominated hegemonic media is where critical fans and antifandoms and disruptakes thrive. Antifan practices are similar to fan practices, except the antifan actions that lead to the creation and perpetuation of these communities are critical acts, rather than celebratory. Within antifandoms, both critical uptakes and disruptakes (Dryer, 2016) are often the anticipated responding actions to both the original cultural material and fan communities. This section will focus on one antifans’ disruptake posted on AO3, specifically a disruptake in response to the GOT fan community.

Jonathan Gray (2005) argues antifandoms are part of the taxonomy of fandoms; antifans are those who express their distaste for a particular piece of media, character, or genre while simultaneously building community and performing their distaste. Gray (2003) frames antifandoms as criticisms, either moral criticisms or criticisms about a texts’ failures. Wanzo (2015) builds upon Gray’s antifandom, tracing a lineage of Black antifandoms as critical spaces for merging how critical reception and fandoms may be understood: “Black Twitter participants can be highly creative; their responses continue a century of media critiques offered by the black public — criticisms archived in the responses of African American politicians and political organizations, in the black press, and by African American writers and entertainers.” Wanzo’s analysis of Black antifandoms demonstrates how antifans critically uptake both fandoms and white-dominated popular culture texts. Antifans’ critical uptakes often explicate how popular culture fails Black countercultures, people, and representations, signaling to Thomas’ “imagination gap” in mainstream media. Florini (2015) in her analysis of #DemThrones points to antifandoms as a necessary perspective for understanding Black fans’ responses and reactions to GOT; while the show is “coded white” and reconstructs white supremacist ideologies, Black fans and fans of color simultaneously enjoy and critique the show, as they often must in white-dominated hegemonic culture.

Both critical uptakes and disruptakes appear in antifandoms, necessary uptakes to both critique and disrupt how popular culture reifies and perpetuates white supremacy. Dylan Dryer defines disruptakes as “uptake affordances that deliberately create inefficiencies, misfires, and occasions for second-guessing that could thwart automaticity-based uptake enactments” (p. 70). Dryer’s taxonomy of uptakes — uptake enactments and affordances — point to how uptakes can work; uptake affordances are the opportunities composers use that “precede and shape” their uptake enactments, while uptake enactments, are the actual actions taken to respond to a genre. Uptake affordances are like writing prompts or questions in a survey, in which composers then respond to through their enactments. Disruptakes, in a sense, are the actions the uptake affordance composers take to force other composers to second-guess or rethink their uptakes, uptakes that may seem second-nature. For example, a teacher may pass out a test in class that asks students to not fill out the test until they finish reading all the questions. The last question, then, is for students to hand in a blank test with just their name at the top in order to pass. This disruptake asks students to rethink how they “take tests,” in that they do not write any responses to any of the questions that normally prompt a written response. Distruptakes and critical uptakes are not one in the same; a disruptake can be critical, and a critical uptake may disrupt, but they are not interchangeable. By forcing other composers to second-guess these seemingly natural responses, the disrupter can use this opportunity to make explicit the tacit ideologies underpinning an uptake and genre, which I call a critical disruptake.

One fans' AO3 post, “Fuck this shit” by Chewing_Gum”, perfectly captures how an uptake may be both critical and disruptive; specifically, Chewing_Gum’s piece demonstrates how Black antifans may use critical disruptake to ensure their criticisms, specifically their criticisms of racism and white supremacy, are heard. Fanfiction may be both an uptake affordance — prompting a response— and an uptake enactment — the response. Some fanfiction composers expect readers to comment on their pieces and invite commentary through their Author’s Notes and recognition of the readers’ responses. Chewing_Gum’s fanfiction is a critical disruptake affordance and enactment, both responding to the GOT fan community and inviting others to respond to her. Her entire “fanfiction” is less than 100 words long and is not actually a fanfiction; she uses the space that would normally be for fictional story-telling to write a post calling out the fan community for ignoring Missandei’s death and Grey Worm’s trauma and demands better.

Almost all posts on AO3 are expected to be fanfiction and stories. The platform is designed to be used by fanfiction writers and prompts composers to write fiction. Before publishing a story, posters choose a title, write a summary of their fic, and choose tags to make their piece discoverable. Chewing_Gum includes all these features — a title, tags, a summary, and her story. Except she does not use the features the platform prompts in a way that others traditionally use these features. For example, her title is “Fuck this shit,” an evocative exclamation with an expletive (fuck) that may intrigue readers to click on, or stay away from, her fanfic. Her summary, too, does not “summarize” the story she tells. It simply says “Fuck 8x04,” referring to GOT season 8, episode 4. Her use of expletives were what originally drew me to her post. The actual body of text, too, is not a story. There is no plot, no reimagination of characters, and no fictional world. She uses this space to critique both the GOT show and the GOT fandom. Her first paragraph says: “Soooooooo D&D wants to kill off the only black women who’s had a story line this whole series so what, Daenerys can finally have an excuse to go Mad Queen on us????!!!!!” She specifically critiques the show and the show’s writers — D&D, or David and Dan, is a common phrase used in the GOT fandom — for killing off Missandei, citing her as the “only black women who’s had a story line.” Chewing_Gum’s frustration here is palpable because she uses AO3 in an unconventional way, writes expletives clearly in her title and summary, and uses the space traditionally meant for fiction writing for media criticism. Her fanfiction also demonstrates how she may feel alienated or unwelcome in the GOT fandom, as fan content is often not created with audiences like her in mind.

What makes this fanfic a critical disruptake is she both uses a platform that is traditionally for writing fiction in order to speak directly to the fan community and addresses the lack of “black love” in the fandom, critiquing how fans value White characters and not Black characters. Her critical disruptake forces readers to pause, not only because her AO3 post is not a fanfiction, but because she explicitly addresses her audience and critiques the lack of Black representation in the GOT fan community. She writes:

Further more, y’all really need to start writing more Grey Worm/Missandei stories because honestly the ones we have now are not the best but they’re a’ight I guess. I just need more black love in this fandom. And I know I’m gonna have a bitch in comments talking about “Well then you should write the stories yourself ” nah hoe, if I could write them trust and believe they would be up right now.

Her criticism of the lack of Grey Worm/Missandei stories points directly to the lack of Black representation and “black love” in the GOT fandom. She prompts readers — making this an uptake affordance — to rethink how they view Missandei, Grey Worm, and the fan community by encouraging them to write fanfiction that celebrates Black characters, cultures, and people. She also anticipates potential responses, saying “I’m gonna have a bitch in the comments...” demonstrating that she believes her post will invite controversy and debate; this also, though, points to the dominance of whiteness in the fandom, one seen in the “Tracing White Supremacy in GOT Fanfiction” section. There is no criticism in the comments, and her readers seem to celebrate her critical disruptake. Her antifan practice, her critical disruptake invites reader response, reimagines how AO3 may be used, and demonstrates why Missandei deserved better.

Conclusion: Why Missandei Deserves Better

Missandei deserved better because Black, people of color, and ally fans are exhausted from seeing their people die in mainstream media, historically, and in current events. Chewing_Gum’s post and Writegirl’s reflection on Missandei’s death demonstrate the affective responses of fans and antifans of color when fandoms reinscribe the white supremacist ideologies in a show. Lady_R and supergirrl’s fanfictions reimagine the representations of white supremacy in GOT to instead protect and value Black characters, cultures, and stories. Critical uptakes, including critical disruptakes, in fandoms are necessary to intervene in racist composing practices both in the original material and the fan community at large. To kill or write off characters of color — specifically Black women like Missandei — can be a violent, political action. And the path towards resistance and healing is carving space to “love blackness” in popular culture, fandoms, and antifandoms alike.

There is no negativity towards her fanfiction in the comments, and her readers seem to celebrate and agree with her critical disruptake. Her fan practice, her critical disruptake invites reader response, reimagines how AO3 may be used, and demonstrates why Missandei deserved better. There are only 11 comments in response to her story, including mine and her responses. Most comments echo her anger and frustration, one commentor writing “PREACH” and two mentioning their own Missandei/Grey Worm stories. Those who engage with her do so because they already have similar perspectives. The rest of the fans ignore her call.