Research Ethics and Positionality

Table of Contents

- Feminist Research Praxis.

- Merging Feminist Praxis and Digital Writing Research

- Why feminist digital humanities?

In her article "Toward a goodwill ethics of online research methods," Brittany Kelley (2016) argues that researchers and teacher publicizing fan texts or communities may expose those communities for trolling, doxxing, and other harmful behaviors. She specifically refers to a fanfiction course at UC Berkeley that published its syllabus in the Daily Californian; fan authors’ URLs and information were made public without their consent, and as a consequence, trolls poured into their inboxes and harassed them.

Online fanfiction is accessible by most people with internet access. These fanfictions are not necessarily available for public consumption because they are held within a space dedicated for fans and are rarely looked at by people outside the community. By publishing fanfiction authors’ usernames and stories, researchers and teachers are making people outside the fan community more aware of these fans’ accounts and spaces, therefore potentially opening these spaces up for harassment. Online and digital community research should always center ethics and justice. Because information and data can be easily scraped off the web, I believe researchers should take time to explain the ethics of their research, receive full and enthusiastic consent from research participants, and explicitly share how their research may impact the communities they are researching. Digital research ethics must center the online communities and users first, recognizing that most people do not post on the internet expecting someone to write an article about their work.

In the edited collection Digital Writing Research: Technologies, Methods, and Ethical Issues, McKee and Devoss (2007) defines digital writing research as research “(a) on computer-generated, computer-based, and/or computer-delivered documents; (b) on computer-based text-production practices (and we deploy text broadly here, to include multimedia artifacts); and/or (c) on the interactions of people who use digital technologies to communicate” (pg 3). Digital literacies and digital writing spaces have shifted how digital participants understand themselves, communities, writing, conversations, and more. What does it mean to be able to access particular information from anywhere with internet access? What does it mean to be able to participate in an online community while remaining anonymous? What is the interdependent nature between writers’ complex digital and non-digital identities?

In this section, I will describe the ethical frameworks that drive my research, who my research and I am accountable towards, and how these commitments impact my research process and product. My research ethics stem from feminist — especially Black feminist — and decolonial research and scholarship. I implement feminist research praxis at every stage of my work, from my citational politics, to my theoretical frameworks, to my interactions with research participants, and finally how I present my work. Because much of my work focuses on critical fans, or fans who often explicitly address harmful ideologies and practices within their own communities, I ensured the fans whose fanfics I analyze and/or who I interview provided full consent before examining their work. I am indebted to the fans who consented to their work appearing in my research, not only because their perspectives help drive my thinking, but because of their dedication and love for fandoms. I have learned so much from them and from all the fans who I have engaged with in my fandom life, ever since I was pre-teen and discovered Yu Yu Hakusho fanfiction on Quizilla.

Digital Feminist Research Praxis

Feminist praxis requires researchers to critically examine their own positionalities, their relationships with people who they research, their research process, and their citational practices when doing this research (Bolles, 2013; Bailey, 2015 & 2018; Ahmed, 2017). I look specifically to Black feminists, whose scholarship often builds upon and makes transparent research ethics and epistemologies. Research ethics are not just about the methods used and the communities studied, but who your research is held accountable to and the types of knowledges that your research both values and perpetuates.

I do not consider my research decolonial as I am not working with Indigenous peoples, cultures, or perspectives. However, decolonial researcher ethics provide an important framework to practice more justice and care-based research. As Leigh Patel (2016) argues in Decolonizing Educational Research, “research is fundamentally relational project–relational to ways of knowing, who can know, and to place” (p. 48). Patel emphasizes that research constructs knowledge and understanding, which can be used to empower groups but also silence and oppress them. The decolonization of educational research encourages researchers to begin asking questions like “why me?”, “why this?”, and “why here and now?” to address the contextual and localized reasons for pursuing this research, as well as directly acknowledging what is gained and damaged when this research is taken on.

I do not consider my research decolonial as I am not working with Indigenous peoples, cultures, or perspectives. However, decolonial researcher ethics provide an important framework to practice more justice and care-based research. As Leigh Patel (2016) argues in Decolonizing Educational Research, “research is fundamentally relational project–relational to ways of knowing, who can know, and to place” (p. 48). Patel emphasizes that research constructs knowledge and understanding, which can be used to empower groups but also silence and oppress them. The decolonization of educational research encourages researchers to begin asking questions like “why me?”, “why this?”, and “why here and now?” to address the contextual and localized reasons for pursuing this research, as well as directly acknowledging what is gained and damaged when this research is taken on.

In terms of my research process, I look to Moya Bailey, whose work centers and advocates for highlighting feminist praxis. In her article, "#transform(ing)DH Writing and Research: An Autoethnography of Digital Humanities and Feminist Ethics," Bailey (2015) describes how she incorporates feminist research ethics in her examination of Black trans women’s online communities. In studying the creation and proliferation of the hashtag #GirlsLikeUs, Bailey reached out to the hashtag’s original creator, had a discussion with her, and also hosted conversations with other Black trans women. She provides a list of potential questions researchers can use to put their feminist values into practice as they research. These questions shape much of my research process as well as thinking through how I would actually present my research. Many of her questions revolve around the researcher viewing research participants as collaborators, not subjects of study. Because of this, I invited all the people I interviewed to look over data with me and share their own analysis. I have also created an entirely digital dissertation (what you are reading now) to ensure that the fans with whom I worked have access to everything I write about them.

Often, dissertations and academic work is hidden behind a paywall, and I believe in making knowledge and research accessible. As I argue throughout my entire dissertation, fans are always-already theorizing about politics and their relationship with popular culture, the source texts, and fandoms. I hope this dissertation contributes to their theorizing and acts as evidence they may use to continue advocating in their own communities. I also hope that other fans, fans who may not consider themselves critical fans or have not thought about the political ramifications of their composing practices, may use this dissertation to think more critically about their practices. How can we continue to reimagine a world that combats harmful systems of power like white supremacy, heteronormativity, and misogyny in our own composing and engagement?

Another important aspect of feminist praxis in research is articulating citation politics. When discussing citation practices and politics, we must also think about the histories and current political ramifications of gatekeeping. Gatekeeping knowledges and resources is one issue Black feminist scholars often point to in academia. First, citations are a form of currency in academia, and who you choose to cite demonstrates your own investments; being cited, too, helps scholars’ ideas to perpetuate across a discipline and can help scholars get jobs and receive promotions (Bolles, 2013; Ahemd, 2017). Besides the transactional nature of citations, though, feminist citational politics reimagine disciplinary epistemologies, though, or how knowledges form and spread. Lynn Bolles, for example, argues that anthropologists, and thus the anthropology discipline, often erases Black anthropologists work, both damaging Black anthropologists’ careers and erasing Black perspectives and knowledges. Bolles argues for the need for, “transformative practice[s]...in the practice of citation,” to combat white supremacy and gatekeeping.

Citational politics are similar to representation politics in popular culture. Who is represented? Who is erased? How are particular people represented? What can we do better? For me, this is the motivation driving my citational politics as well as the particular television shows and characters I choose to research. For instance, I prioritize Black feminist scholars like bell hooks, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, and Moya Bailey in my citations, and also focus on characters of color, specifically women characters of color, and canonically LGBTQ+ characters. I see the politics of representation — both in popular culture and fandom — as I see citational politics. Whose stories and perspectives we expose ourselves to drive how we see and understand the world?

Merging Feminist Praxis and Digital Writing Research

Ethical research may fall anywhere from following Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol to creating a code of ethics based specifically on the research context. The IRB is an ethics committee housed within institutions, including universities, to ensure researchers follow a series of ethical protocols and do not harm people, particularly vulnerable populations such as people who are currently incarcerated or children. IRB protocol must be followed in any institutional research, but IRB does not always cover the complexities of ethics in digital writing research or in its definitions of vulnerable populations. For example, Banks and Eble (2007) describe IRB’s inability to capture the nuances and complexities of digital writing research because when guidelines were written, the internet was not as prevalent and part of our everyday experience. They discuss relying on IRB for ethical protocols, but also working with institutional IRB reviewers to create a more specific approach to ethical research. IRB is not the last stop for following a code of ethics, however, especially with digital writing research.

The CCCCs Guidelines for the Ethical Conduct of Research revised in 2015) has an entire section dedicated to online research. CCCC’s guidelines encourage researchers to think about anonymity (or lack of anonymity), accessibility, and better understanding the public/private binary. Specifically, these guidelines suggest articulating all steps of the research process to participants to confirm they are aware of and comfortable with potential risks. I let participants know that their works were linked in the dissertation and some of their usernames were used, which brings their piece to a potentially more public light. As most fan authors publish on AO3, they are more familiar with how users take up their pieces. Because there is also a ton of content on AO3, some of their work may go unnoticed except by those actively seeking it out because these readers are invested in what the authors are writing. However, by bringing their usernames and stories out from the AO3 space, there is always a risk of an unfamiliar reader who reacts poorly to their work. I informed the authors whose names are mentioned of the risks and ensured that information can be taken down from the CFT if need be.

Besides CCCCs guidelines, the Association of Internet Researchers hhas created more specific guidelines for people interested in conducting digital research. The AIR has come up with “key guiding principles” that are critical when thinking about digital research and digital writing research:

- "The greater the vulnerability of the community / author / participant, the greater the obligation of the researcher to protect the community / author / participant."

- "Because ‘harm' is defined contextually, ethical principles are more likely to be understood inductively rather than applied universally."

- "Because all digital information at some point involves individual persons, consideration of principles related to research on human subjects may be necessary even if it is not immediately apparent how and where persons are involved in the research data."

- "When making ethical decisions, researchers must balance the rights of subjects (as authors, as research participants, as people) with the social benefits of research and researchers' rights to conduct research."

- "Ethical issues may arise and need to be addressed during all steps of the research process, from planning, research conduct, publication, and dissemination."

- "Ethical decision-making is a deliberative process, and researchers should consult as many people and resources as possible in this process,...where applicable, legal precedent."

These guidelines continue by exploring more specific contexts of digital research in hopes of tackling the ethical issues that may come up throughout digital research. What is most important for me is to better understand the impact digital research may have and weigh the impact of this research. If there is any potential for harm — especially revealing or making public vulnerable communities and ideas — further discussion should be had with community members. With all digital research, there is a person behind the digital content, a person who has made choices and published particular ideas.

For my research, I went through IRB to create consent forms, but also took the extra step to invite participants to review what is available on the CFT to ensure it reflects their views and perspectives accurately and safely. For instance, even if a fan author consented to allowing me to write about their work, I still continue to reach out to them, sending them individual pages where their usernames or aliases appear. The six fan authors who I interviewed each received the “Interviews” link, where I offered them a chance to look over the transcripts, my analysis, and even their self-chosen demographic information. Another example is in the “Case study” section, where I reached out directly to the authors whose work I mentioned. By emailing them, I hope to encourage back-and-forth dialogues and also recognize that some fan authors may not have the time for dialogue. I keep this option open, though, in case they want to make changes in the future to their consent.

Turning back to the community, presenting findings, and allowing for dialogue, is one of the central steps all researchers must take. The best approach is to work with and pay community members. This, of course, can be difficult for smaller projects or graduate students who may not have grant money. If researchers have the resources like grant funding, inviting community members to conduct research with you is even better.For instance, I received a small grant from the NULab at Northeastern University and paid interview participants for their time and labor.

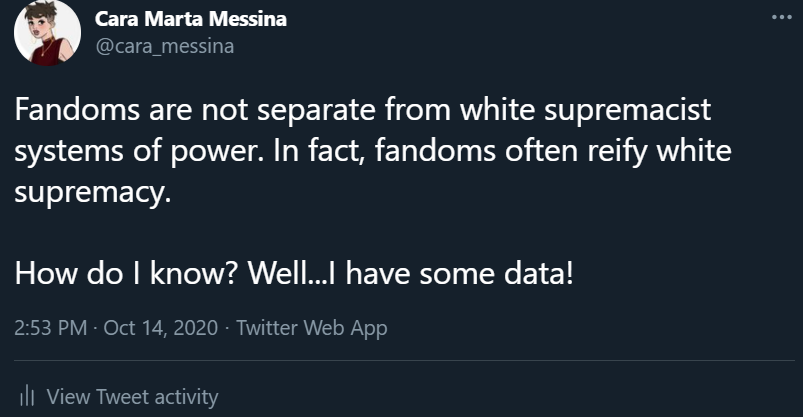

Finally, I also turn to Twitter to share my findings, hoping to get feedback from casual, immersed, and academic fans. For example, I did this with my findings on how GOT fandoms unintentionally reinforce white supremacist systems (Figure 1).

Like most researchers in academia, I try to ensure the safety of all my research participants. However, researchers and practitioners can wind up enacting harm on participants unintentionally. Reviewing IRB guidelines is necessary, but just the first step. Who are your research benefactors? How does your research help the community or people you are researching? Does the community you’re working with want or need that research? And are you the right person to be doing that research? I feel comfortable working with fanfiction data because I have been a member of multiple fan communities for almost two decades.

However, I also recognize my position of power here because I am an academic, a cis White woman, and getting paid to do research. My perspectives may unintentionally invalidate or enact violence upon fan community practice. The goal for all researchers, not just those committed to feminist praxis, should be to benefit and protect the communities with whom we work, especially historically and politically marginalized communities. I hope by sharing my own process engaging with other feminist researchers like Bailey and Kelley, following and implementing ethical guidelines, and describing the back-and-forth communication with members provides an example for other researchers to follow. Our research practices are political.